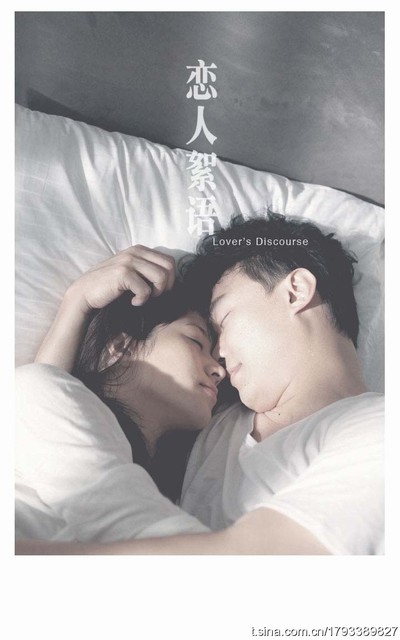

In Guo’s trapping of the humorous minutiae of language and loss, she opens her literary borders to a playful and nuanced meadow. Guo’s prose has a plain, precise, and somewhat documentary quality. A Lover’s Discourse examines what it is to be alone within language and burrowing into a new language, while reconciling it with your native tongue. Within this she calmly considers the meaning of artistic authenticity in the age of mass production. Her new arrival faces a society that cannot agree on its own boundaries or nature, apparently at war with itself. Guo keenly inverts the anthropological gaze onto the British, their language and other cultural peculiarities. More important than this nod to Barthes, though, is the novel’s own singular linguistic texture and the ongoing jolt of its political setting. shares its title with Roland Barthes’s A Lover’s Discourse, and like Barthes’s book it takes a fragmented form, that of casual conversations, mostly between two lovers. She is in a relationship, even in love, but often alone, wordless, unable to express what she wants.

Similarly, Guo’s writing preserves this remove through definitions and questions, reminding the reader that the language it is written in has been studied and learned. This reserved filming keeps the viewer a step away from what she is seeing we may feel a little like we’re attending a party where we don’t know anyone and are straining to put together who is who. The time we live in is not defined by a shared humanness but by the fact that no one is truly at home where they are. She seems interested not in some sense of 'the world' but in a question of what it might mean to be international. Her books do not privilege storyline but take a more documentary approach. Guo’s novelistic writing is not particularly narrative, or linear, or uplifting. She has spoken out against the self-censorship caused by authoritarianism, but also the kind created by the demands of the market.

Guo seems interested in describing distance rather than points of commonality, capturing an inability to talk rather than a global conversation. The work of Xiaolu Guo both plays with this globalization of literature and rebukes it. Guo gives her characters scope to live and suffer, so her book’s final affirmation has a hard-won quality that carries weight. Along the way, it’s capacious enough to touch on moments of real darkness, while somehow managing to be mordant, funny and, ultimately, life-affirming. The book moves briskly from the canals of North London to Scotland, Australia, Germany and China. What propels the book forward is in part the sense of suspense that hangs over the nascent relationship: Has our heroine made an enormous mistake getting together with an itchy-footed boat lover? But there’s also something compelling about the breadth of the world the narrator inhabits. There are shades of Lydia Davis in her carefully etched sentences as she details the ups and downs of the relationship without sentimentality. The truthfulness and accuracy of Guo’s language gives the book mischief and energy. She paints a vivid but unflattering portrait of her new dwelling in her adopted country.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)